Valley fever can infect both humans and dogs. In the second and final installment of our series examining valley fever, you’ll hear the story of Cooper, a boxer mix from California’s Central Valley. He nearly lost his life to the fungal infection. In this episode of Unfold, we’ll talk to UC Davis scientists working across medicine and veterinary care to study valley fever. You’ll hear not only about one dog’s fight for survival but how dogs may hold the key to predicting valley fever’s spread in humans.

In this episode:

- Dr. Jane Sykes, small animal veterinarian at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine with a special interest in infectious diseases

- Dr. Glynn Woods, Veterinarian, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

Omar and Rosemary Rios, owners of Cooper, a dog with valley fever

Learn more about valley fever in both dogs and humans in our in-depth In Focus feature.

Transcript

Transcribed using AI. May contain errors.

Omar Rios

He's super friendly.

Amy Quinton

Cooper, a four-year-old boxer mix, was excited to have visitors at his home in Farmersville, a small town in California's Central Valley. He immediately brought me a stuffed toy. Omar and Rosemary Rios are his human parents.

Marianne Russ Sharp

They adopted him when he was just a puppy, and from the beginning, Omar says he was more than a pet.

Omar Rios

He's not just a dog. People know him. People go to the store, where sheworks, and ask for him, and I go, where's Cooper? I came here just for Cooper. So he's like, yeah, he's just a member of the community, and he's family to us.

Amy Quinton

Rosemary runs an athletic store. She's a runner, and so is Cooper, several miles a day.

Marianne Russ Sharp

So just a year ago, when Cooper's energy started to dip, the Rios's began to worry. He wasn't eating much, but his belly looked full.

Rosemary Rios

after a hike, which he did great on later that evening, when he came home, he had shortness of breath. He was like labored to breathe, and that's when we knew something had to be wrong with him.

Amy Quinton

In fact, that's what you're hearing right now, Cooper struggling to breathe. Rosemary recorded much of his illness.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Their local veterinarian found fluid had built up in his abdomen. Ultimately, they rushed Cooper to UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital.

Rosemary Rios

It was absolutely terrifying as we drove to UC Davis, we really didn't know what we were going in for, but knew that we were willing to do whatever we could to help him.

Marianne Russ Sharp

The diagnosis caught the Rios's off guard: valley fever, a fungal disease. It was one they had heard of, but only in humans.

Amy Quinton

But dogs also get valley fever, and it's showing up in unexpected places.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And as scientists are learning, dogs may be the first to warn us when the fungus is spreading.

Amy Quinton

Dr Jane Sykes is working with researchers and physicians at the Center for Valley Fever at UC Davis Health.

Marianne Russ Sharp

She's a small animal veterinarian with a special interest in infectious diseases.

Jane Sykes

Dogs are close to people. There's lots of dogs. They dig in soil, which puts them at risk of the disease, and so they're potentially really good sentinels or signs that humans might also be getting infected in in a region.

Amy Quinton

In this episode of unfold, you're going to hear not just about one dog's fight for survival. We'll tell you how dogs may hold the key to understanding valley fever and its spread.

Amy Quinton

Coming to you from UC Davis

Marianne Russ Sharp

and UC Davis Health

Amy Quinton

This is Unfold. I'm Amy Quinton.

Marianne Russ Sharp

and I'm Marianne Russ Sharp.

Amy Quinton

The Rios's drove Cooper almost four hours through the night to try to make it to the UC Davis vet hospital before 11 that evening,

Marianne Russ Sharp

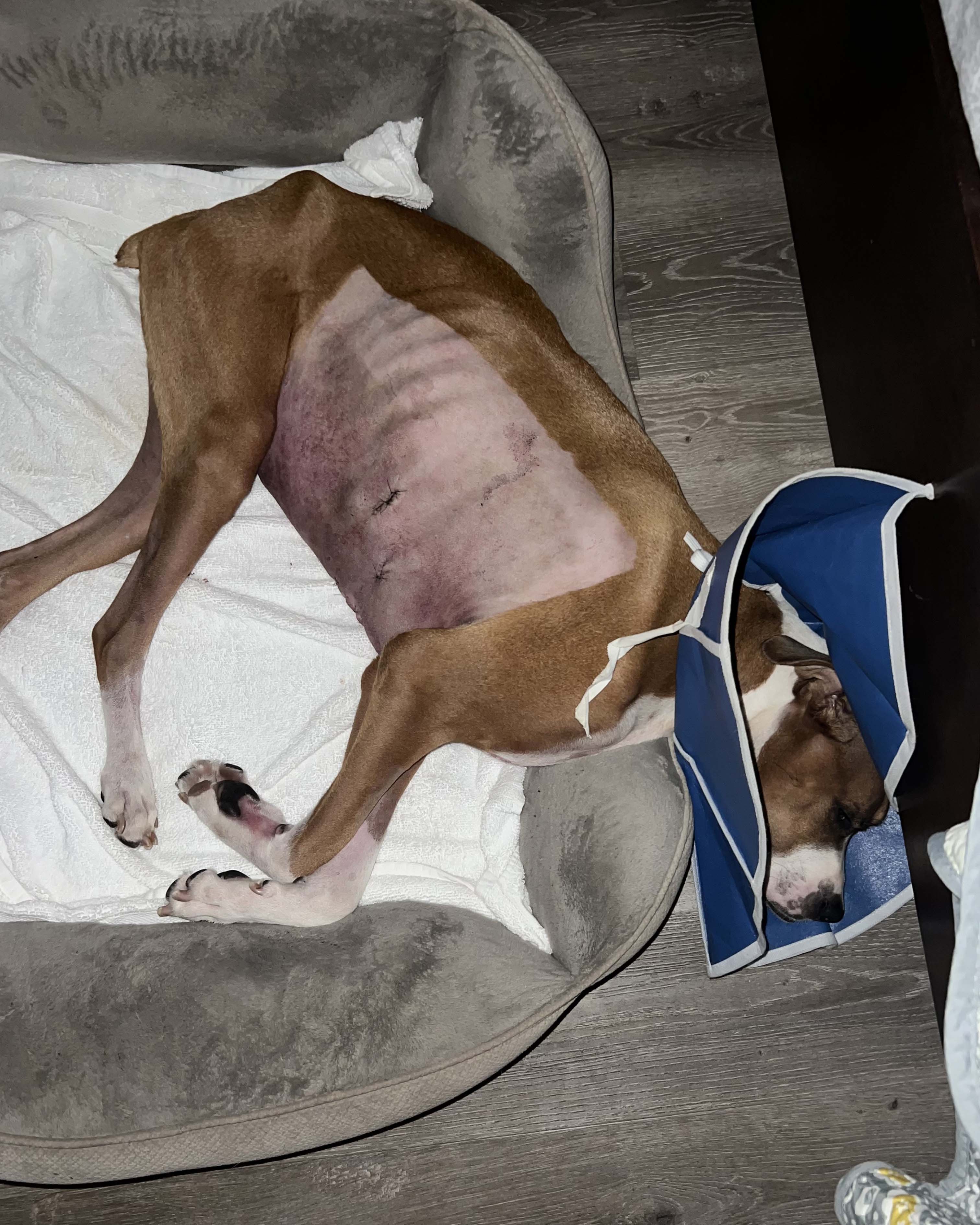

Once there, veterinarians drained the fluid that had built up in Cooper's abdomen because of the fungal infection, three liters in all.

Amy Quinton

Dr Glynn Woods, who would become Cooper's main veterinarian, says cardiologists were suspicious that the fluid wasn't coming from his abdomen, but instead his heart.

Glynn Woods

The pericardium, this really tiny layer that encompasses the heart, was markedly thickened, thicker, as almost as thick as my thumb when it should be, you know, cells thick just to gently coat the heart. It was grossly abnormal. And I was like, 'oh my goodness, this is shocking.'

Marianne Russ Sharp

Veterinarians faced a tough decision. The primary treatment for valley fever in dogs and humans is antifungal therapy.

Amy Quinton

But Cooper's heart condition was severe, he needed surgery. Which treatment should come first?

Marianne Russ Sharp

They decided to give Cooper antifungals and wait.

Amy Quinton

But Rosemary says vets told her Cooper just wasn't improving fast enough.

Rosemary Rios

They felt he needed to have the surgery as soon as possible, because he was still filling with fluids and having to drain him so much.

Amy Quinton

they were draining liter after liter and the fluids were putting pressure on his organs.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Surgery would also be risky. Cardiologists found that Cooper's pericardium had adhered to his heart, making it too difficult to remove.

Glynn Woods

What they ultimately done was just create a huge window in the pericardium so it effectively cut a hole delicately into the pericardium to allow the fluid that was entrapping the heart just to flow into the thorax and immediately relieve pressure on the heart.

Amy Quinton

The surgery was successful. Rosemary filmed the moment she and Omar finally saw Cooper after surgery.

Amy Quinton

Cooper, his abdomen shaved, eagerly walks over to them, wagging his tiny tail

Marianne Russ Sharp

Within just a few days, Cooper went home.

Omar Rios

Cooper, you ready to go home? Finally going home after 5 days.

Amy Quinton

But this wasn't the end. It was the start of a marathon.

Glynn Woods

It wasn't a joke how significant the disease burden was on Cooper. The dog still had to fight the fungal infection, which was draining him systemically. We were so chuffed that he came through the surgery well. Then we realized, wait now is the long game.

Marianne Russ Sharp

He would still have to endure numerous antifungal treatments with the drug Amphotericin B, which can be toxic to other organs, and the fungal infection was still causing fluid to build up in his chest.

Amy Quinton

He'd lost 15 pounds and wasn't gaining it back.

Rosemary Rios

There were so many times where we didn't think he was going to make it through. I remember even after his the surgery and continuing treatment. There was a couple times where Dr Woods looked scared and concerned, and he kind of said, well, this really concerns me. We're gonna have to see what happens after this treatment.

Glynn Woods

It's really difficult for me to hide my feelings, and I think the owners were had already come through a lot, but when I kept seeing this dog's weight go down, you do feel you're losing the battle, but we just had to, like, stay the course, give this dog time.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Rosemary was able to drain fluid from Cooper through ports that were surgically placed in his chest.

Amy Quinton

That allowed him to get better at home, rather than making multiple trips to the hospital.

Marianne Russ Sharp

It bought them time. They were all in and Cooper kept fighting.

Amy Quinton

The severity of Cooper's valley fever is rare, but Dr Jane Sykes has seen plenty of dogs with severe valley fever at UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital.

Marianne Russ Sharp

One fungal spore is all it takes to cause infection. She says it usually starts with respiratory signs in dogs, just like in humans. And there are other similarities too.

Jane Sykes

I think we have the same problems as they do in human medicine in dogs, and oftentimes veterinarians are not thinking about valley fever as a diagnosis. And I've had dogs that have been referred up to me because they've been diagnosed with like chronic kennel cough, when in fact they have valley fever.

Amy Quinton

Sykes says valley fever is common in animals, particularly with dogs that like to dig. But she wanted to find out just how prevalent the infection was and whether dog cases could tell us more about the fungus's spread.

Marianne Russ Sharp

She looked at nearly 900,000 blood antibody tests from dogs that had been tested for the infection.

Amy Quinton

They were from across the US between 2012 and 2022. Cases in that time increased as expected. But what else she found amazed her.

Jane Sykes

The first big surprise was just the proportion of animals that tested positive, so we had nearly 38% of the test results were positive. And that's really high when you compare it to other infectious disease studies, where you might see, you know, less than 10% of animals testing positive.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Then, working with colleagues at UC Berkeley, she used the data to map the locations of dog cases.

Jane Sykes

Creating the actual maps actually doesn't take that long. So we're all holding our breath, thinking, what is this going to look like? Is it going to look like what we know about the maps for humans? And then these maps came up, and they were just perfect in terms of what you would expect, what we know about the distribution of the fungus in people.

Amy Quinton

What was perhaps more surprising, positive cases were turning up in states where valley fever is not considered endemic.

Marianne Russ Sharp

The Centers for Disease Control considers it endemic in parts of six states; California, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas and Utah.

Amy Quinton

The study also provided insight on its spread in states that aren't required to report human valley fever cases, like Montana and Texas.

Jane Sykes

All of a sudden, we were given this window into what might be going on in these states to know where human disease might be occurring, because now we could see it also in Texas, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, some signs that it could be present in people that might be getting it in those locations without traveling.

Marianne Russ Sharp

She found cases of valley fever in dogs in Washington and Colorado as well. And Sykes says they also compared dog and human cases in both California and Arizona.

Amy Quinton

Both states are known hot spots for the infection. She found the similarities striking.

Jane Sykes

So that was amazing when we saw just how close it was, and a sign that dogs really might be able to help us understand, you know, disease in humans as well.

Marianne Russ Sharp

And that's the next step in her research. She wants to use the data to see what factors besides digging in soil put dogs at risk for contracting valley fever. Could it be similar in humans?

Jane Sykes

There may be, even within that group, these genetically susceptible breeds, and if we can understand the genetic mechanisms of susceptibility in dogs, which have quite homogenous genomes compared with people, then we might be able to also get understanding about genetic risk factors in people.

Amy Quinton

Ultimately, she hopes the data will better protect both pets and people. It's part of a One Health approach, the idea that human, animal and environmental health are all connected.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Back in Farmersville, Cooper is still on antifungal medication, but he's back to his normal weight. He still has ports under his skin, a reminder of all he's been through.

Amy Quinton

Omar Rio says until Cooper was infected, he never knew dogs could get valley fever.

Omar Rios

Most people that we talk to that are dog owners. They don't know as well. Even the doctors, when we took them to a local vet, they did not suspect that it was valley fever they thought it was cancer.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Since then, Omar says valley fever is top of mind for his local vet.

Amy Quinton

Cooper's fight against the infection showed his family and his veterinarians what it means to push through even when the odds were stacked against him.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That left an impression on his care team at UC Davis, including on Dr. Glynn Woods.

Glynn Woods

This dog never moaned. This dog sat there, let me poke and prod, and he's just got this most like docile little face where he just almost stares at you like he's bored, and as he got brighter, you could see his tail starting to wag, and he was like his little bum was shaking. Em, so no, he was he was always in good spirits despite being profoundly unwell.

Amy Quinton

And no one knows his resilience better than Rosemary and Omar Rios.

Rosemary Rios

He is a miracle for sure. He's a fighter, huh Cooper? Yes, you're a fighter.

Marianne Russ Sharp

He's also still a runner. He's not running miles a day like he used to, but Rosemary recorded this joyful jog they took together on Christmas Day.

Rosemary Rios

Good job Cooper, yeah you're running. You're running.

Amy Quinton

And there's more good news. Scientists are hoping to soon bring a vaccine to the market that prevents valley fever in dogs.

Marianne Russ Sharp

It's yet to be approved by the USDA, but researchers are hopeful it might happen soon.

Amy Quinton

And if you want to feel really hopeful, a little bonus track.

Marianne Russ Sharp

I do want to feel hopeful

Amy Quinton

okay. Well, we can't end this podcast episode without sharing the joyful sound of Cooper doing his favorite activity, chasing water from the hose.

Omar Rios

He loves the water. If he gets it, he loses interest if I let him get it too much. He'll play all day.

Marianne Russ Sharp

Oh, that's awesome. I love it.

Amy Quinton

If you want to see photos of Cooper and the Rios's, visit our website.

Marianne Russ Sharp

That's where you'll also find a link to a longer story and video about what UC Davis is doing to help both dogs and humans with valley fever. I'm Marianne Russ Sharp.

Amy Quinton

And I'm Amy Quinton. Thanks for listening.

Andy Fell

Unfold is a production of UC Davis. It's edited by Marianne Russ Sharp. Original music for Unfold comes from Damien Verrett and Curtis Jerome Haynes. Additional music comes from Blue Dot sessions.